Founded in 1986 in Mexico City, Enrique Norten's practice TEN Arquitectos is not known for a signature style, preferring to make each project a modernist-infused response to its own specific conditions. Nonetheless, they have become one of the most widely-recognized architectural practices emerging from Mexico, with projects throughout North America. In the latest interview in his "City of Ideas" column, Vladimir Belogolovsky speaks with Norten in New York to find out how the architect's past has influenced his current design work, and to discuss the future trajectory of architecture.

Vladimir Belogolovsky: How busy are you now, what kind of projects are you working on?

Enrique Norten: Fortunately, we are very busy. Half of our work is for such clients as cultural institutions, education, and government. The other half is for private clients – developers and homeowners. TEN Arquitectos maintains around 75 to 85 architects between our two offices in Mexico City and here in New York, from where we are working on projects in many major cities in the US and now in Toronto, and in the Caribbean. Two thirds of the work is handled by our Mexico City office, from which we work on projects all over Mexico and in Central America.

VB: Could you talk about your relation to Mexico? Your work does not scream “I am Mexican!” Is it intentional on your part to be universal and not to be identified with your origins?

EN: It is more complex than that. I was born and raised in Mexico. I graduated from Universidad Iberoamericana and became an architect in Mexico City. Then I came to the States. It was a unique moment. I belong to the first post-1968 generation. I started at university in Mexico in 1972. There was a lot of energy, a lot of questioning... For a long time Mexico had been a closed country. No one was looking outwards, not only in architecture but in all realms of life and culture. But I was always wondering about how things were outside. I was always very impatient. Also I never belonged to the so-called establishment in architecture. I grew up in a middle class family with both sides of my family coming from Europe. So culturally, I was very open.

VB: You went to Cornell, graduating in 1980. Why Cornell?

EN: For two reasons. First, it was a great moment of thinking at Cornell, led at that time by historian Colin Rowe who explored new ideas about the city and rationalist architect Mathias Ungers. The second reason is that it is such a beautiful, bucolic place. It was a world away from what I always knew, a huge, intense city as opposed to an open landscape... Hills and rivers, and lakes, and gorges... Absolutely gorgeous place, nothing like I have seen before. So when I decided to go away for two years, it was a great place for thinking about architecture and reflecting on many thoughts.

It was not intentional that I didn’t want to identify myself with Mexico, but at the time, we had two main currents of thinking. One was Luis Barragán, Ricardo Legorreta, and many others who opposed to pure functionalism and strived for emotional and serene modernist architecture with creative use of color and light. And the other direction was a kind of neo-brutalist architecture led by such architects as Teodoro González de León and Abraham Zabludovsky. I would say their architecture was a bit forced toward pre-Columbian precedent. So these two directions were understood as being Mexican architecture.

My generation did not believe in such limitations. Perhaps that has to do with our rebellious nature and romanticism that was in the air at that time. You know, Mexican art doesn’t need to be Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo only. They were great artists, but they represented their time and their ideas. So I wasn’t comfortable with following anyone. I wanted to find my own spirit. And I found it in the teachings of both Rowe and Ungers. That was the beginning and then, of course, it took decades to find my vocabulary and refine it.

VB: Could you reflect on what you learned from Rowe and Ungers at Cornell?

EN: They were both mentors of mine. By the way, Cornell was very much divided – you were either with Rowe or Ungers, but I learned from both. I took Ungers’s design studio and was meeting with Rowe socially, but Colin was a kind of person that it was all about social. We met at his house all the time. What I learned from him was never to see architecture separately from the city and also history became very fluid to me. Before I saw history as a very boring, almost arithmetic sequence of events, but he made me see it as completely intertwined and interrelated condition. Ungers was a very rational, brilliant architect with very strict rules about geometry and order. He taught us by bringing real competitions into the studio, many residential projects in Europe. And we even won some. [Laughs.]

VB: What do you think about contemporary architecture in Mexico?

EN: It is quite healthy and very vital, and there are many strong architects working in Mexico today. We had a fantastic Modern movement during and after World War II when many European architects moved to Mexico, as well as to other Latin American countries. There was such an amazing flourishing of Modern architecture, as was so powerfully attested at MoMA’s recent exhibition, Latin America in Construction. So we have very strong tradition in architecture and it is now being reevaluated. In the past, it was sort of neglected internationally. Architects practicing in Mexico today are very diverse and their inspirations are coming from all over the globe. Among our leading architects, I would name Alberto Kalach, Michel Rojkind, Fernanda Canales.

VB: Since you studied both in the US and Mexico, I am interested in your view on how the two schools and education systems can be compared?

EN: Completely different... Schools in Mexico, as in Europe are more technical. In Mexico, you graduate and you are an architect. In the US, you don’t automatically become an architect. You need to get experience, pass professional exams, and on and on. So I came out from Mexican university with a very good technical education. I knew construction, material, and so forth. But I was very weak on humanistic aspects of architecture. I did not have opportunities for thinking about architecture, theorizing, interpreting its history, questioning many other of its aspects. Cornell opened for me many doors that I didn’t know existed. And after I left Cornell I never really left. I always kept a very strong relation with the academic world and very soon, I was invited to teach all over the United States. After about 15 years of teaching, frequent international publications, and winning occasional competitions, I started getting commissions here. So it was inevitable that I would extend my practice into the US, which led to opening my office here in New York around 2000.

VB: In 2012, David Chipperfield chose “Common Ground” to be the theme of the 13th Venice Architecture Biennale. That was the acknowledgment that there is no longer such a thing as common ground. Otherwise, why would the director of a major international architectural forum pose this question? Still, would you say that you see yourself as part of a particular architectural school of thought or movement, or are you addressing your own questions and developing your own architecture, and moving in your own direction?

EN: I am not sure there is no common ground... I believe, one thing everyone is doing now is reinventing modernism in his or her own way. Some architects will not admit this, but we all are looking for inspiration in the work of the great masters of Modernism. And then, of course, the issues of natural environment, urban environment, social inclusion... Architects today have greater responsibilities for our work than our predecessors. These are all our common interests.

VB: Well, of course, we are all now converging on paying attention to all these issues. But I am talking about formal aspects of architecture. Do we have common ground formally?

EN: Well, in that sense we are all over the map... But I don’t worry about that now. I am pursuing my own way of doing architecture and sometime down the line, somebody like you will analyze all of us and I am sure, some common threads will be found.

VB: But you don’t feel being a part of a particular group of thinkers who are close to you ideologically and experimentally?

EN: I don’t think so. I believe that romantic time of heroic manifestos doesn’t exist anymore. I can’t imagine being invited to a gathering where we would need to come up with ten points for new kind of architecture. That is gone... For example, tonight I will be having dinner with Thom Mayne. Earlier this week I had dinner with Steven Holl. We are friends.

VB: Do you talk about architecture?

EN: Sure.

VB: Do you argue?

EN: Sometimes. But in a casual way. We don’t contradict each other. We get attracted to some projects and are discouraged by others. Does that mean we are part of a consolidated group? Of course, not. There are no longer TEAM 10 or others. We don’t belong to any groups and we don’t need manifestos. At least I am not aware of any such associations.

VB: Aaron Betsky said about your work that it represents its own poetic brand of Modernism. What do you think about that statement?

EN: Well, it is very generous of Aaron to say that. I am a big believer in Modernism. I like to look at Modernism with the belief and conviction that it still has not given everything. We should continue looking for new possibilities, new responsibilities, and new opportunities within the realm of Modernism. There is a long way to go and in a way, we are all doing it.

VB: To reinforce your point, in one of your interviews, you said, “We are still basing our work on the vocabulary of a century ago, which is the vocabulary that formed Modern architecture.” What about parametrics and other new possibilities in architecture-making - how do you respond to those forces?

EN: Obviously, there are so many new ways of doing things, understanding space, modeling space. All of these discoveries are informing our work very strongly. But personally, I don’t even know how to use those new digital tools. And I am probably the only one in my own office who can’t use them. But in short, I am still much more influenced by the work of the Modernist fathers.

VB: In other words, you start your designs by putting some lines on a piece of paper. You start from scratch instead of responding to some self-propelled, self-generated image on the computer screen.

EN: We don’t do that here. I don’t know how...

VB: Every project starts with your personal sketch.

EN: Yes.

VB: Is there one particular project that would qualify as your manifesto?

EN: I don’t think so. Every project informs the next. I reference some of my past projects all the time because often you can’t push certain ideas and strategies to their full potential, so you revisit them in later projects. We go back and forth. We have done over 300 projects, 50 of which were built, so we have developed a huge database that we refer to and advance all the time.

VB: Do you have one favorite contemporary building?

EN: No, I don’t. I couldn’t name just one. We are interested in a number of offices that we follow.

VB: Could you name just one architect that you admire more than others?

EN: There are many. Most people that I follow are my friends.

VB: When you say follow, you mean you visit these architects’ buildings?

EN: Sure. We visit them together. I already mentioned Thom Mayne and Steven Holl. We visit each others' buildings all the time.

VB: What about Hadid and Gehry?

EN: I know them well. But I am less interested in their work.

VB: You think their work is bombastic?

EN: I would say bombastic is a good word.

VB: And Mayne is less bombastic?

EN: He is more rational. Look, I just saw Gehry’s new Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. I appreciate it, but I am not interested in a series of works that were done before the last recession that demonstrate such extravagance, access, expenditure... And in the end, what does it bring to architecture?

VB: I don’t know, maybe a sense of adventure?

EN: And surprise. And spectacle.

VB: What’s fascinating is that there is no end in this craving for adventure. There is a huge demand for inventing new kinds of experiences.

EN: Yes. It is a strange thing. Architecture has become a destination. But I don’t think the weirdest is the best. I don’t think you need to do the strangest thing, the most unexpected thing in order to do good architecture. Look at the work of Renzo Piano and David Chipperfield. They are very good and responsible architects who don’t base their work on the element of surprise. Is that a good question to ask – how can I do something that had never been done before? I think a number of very intelligent architects are falling into this trap of constantly trying to overdo what they have done before and what others have done. Where does that lead and where does that end? And then you visit a building by Piano and you get a very rich experience from something that is very restrained and simple, like his beautiful Menil Collection in Houston. So architecture is not a competition of strange objects.

VB: Your Guggenheim Museum project in Guadalajara that won an international competition in 2005 was a tall tower with floating galleries. The idea was for the building to occupy as little footprint as possible. Could you talk about vertical organization for this museum?

EN: The solution was in a form of a vertical stacking of solids and voids, meaning enclosed galleries and spaces in between the galleries with various opportunities for exhibiting art in nontraditional ways and settings. It is like a collection of smaller museums within a bigger museum, a vertical landscape within the structure.

VB: What words would you choose to describe your work?

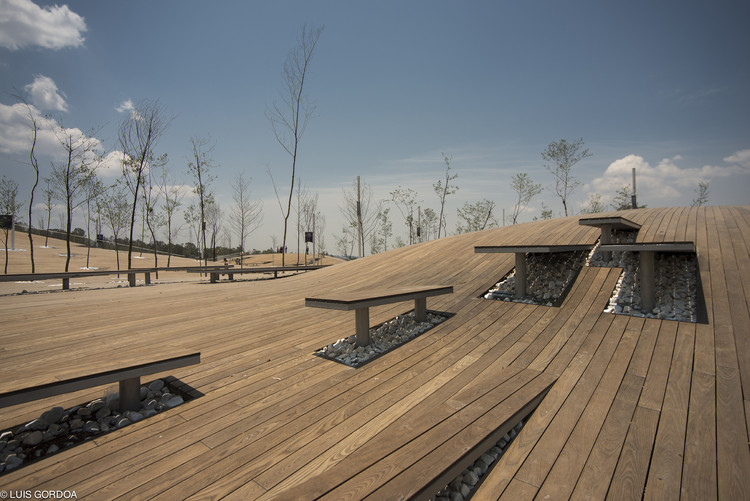

EN: Public space, which are the voids both within and around architecture. Landscape. Topography. Infrastructure. So it is architecture as public space. Architecture as landscape. And architecture as infrastructure. I want architecture to shift focus from its preoccupation with form and object making to public space making.

VB: But your Guadalajara Museum is an object, right?

EN: Yes, an object in a pristine landscape. Now we are finishing a much bigger project, which is completely the opposite and totally about landscape and topography. It is the new Acapulco City Hall, which brings together many city agencies into one building, integrating various departments through open and shared public spaces. It is interesting to contrast these very different projects, which shows that every project leads to different solutions.

VB: What do you think about signature architecture? There is a much greater emphasis now on issues of atmosphere rather than object, issues of connectivity more than autonomy. Personally, I think one should not exclude the other. For example, Piano’s Whitney Museum finished recently here in New York is all about atmosphere. Architecture completely stands back and dissipates. Where do you stand on this and how do you find your own balance between creating an atmosphere and a distinctive object?

EN: It is a big question in architecture now. I’ve been to this building several times and you are right. It is a great experience, but when you leave, you can’t remember the architecture. Still, what works for me in this building is the ground floor. It integrates seamlessly with the city – the plaza, the High Line, the river, the restaurant, the bookstore, the lobby... They become part of the city. And personally, I am more and more interested in the experience than in the object. In the beginning, I was more interested in the object. But what is more important to the people who visit a city – to take with them that iconic form that they will never forget or the unique experience? I like the kind of architecture that underlines and enhances our experience. I agree that the Whitney is not the Menil, but it takes the skill of such great architect as Piano to give us these new ways and opportunities of looking at the city, responding to art, socializing... Formally, he could have done a better job, but the opportunities are there and they are unique. They did not exist before.

VLADIMIR BELOGOLOVSKY is the founder of the New York-based non-profit Curatorial Project. Trained as an architect at Cooper Union in New York, he has written five books, including Conversations with Architects in the Age of Celebrity (DOM, 2015), Harry Seidler: LIFEWORK (Rizzoli, 2014), and Soviet Modernism: 1955-1985 (TATLIN, 2010). Among his numerous exhibitions: Anthony Ames: Object-Type Landscapes at Casa Curutchet, La Plata, Argentina (2015); Colombia: Transformed (American Tour, 2013-15); Harry Seidler: Painting Toward Architecture (world tour since 2012); and Chess Game for Russian Pavilion at the 11th Venice Architecture Biennale (2008). Belogolovsky is the American correspondent for Berlin-based architectural journal SPEECH and he has lectured at universities and museums in more than 20 countries.

Belogolovsky’s column, City of Ideas introduces ArchDaily’s readers to his latest and ongoing conversations with the most innovative architects from around the world. These intimate discussions will be a part of the curator’s upcoming exhibition with the same title to premier at the University of Sydney in June 2016. The City of Ideas exhibition will then travel to venues around the world to explore ever-evolving content and design.